Introduction

Most runners know they “should” strength train. Fewer know how strong is strong enough.

And that’s where things fall apart. Without objective benchmarks, runners either:

- Do too little strength work to matter, or

- Add random exercises without knowing whether strength is actually a limiter

This article focuses on measurable strength standards for runners, grounded in force-based testing and clinical patterns we see every week – and briefly touches on the movement standards that need to accompany those numbers.

After reading, if you still need help, you can contact us!

Why Strength Standards Matter for Runners

Running is often described as a submaximal task due to the speed of the movement in comparison to sprinters or other field-based sports – but that framing hides the real problem.

Yes, each step is submaximal. But it’s repeated thousands of times per week, under meaningful load.

Some context that matters:

- Running-related injury rates are reported anywhere from ~20–80% per year, depending on the population studied

- Each foot strike exposes the body to roughly 2–3× bodyweight ground reaction forces

- Over a typical run, that’s thousands of loading cycles through the same tissues, in the same patterns

- Even muscles we think of as “accessory” muscles like the psoas major undergoes up to 5-10x body weight in compression during sprinting (Bogduk et al 1992)

If a runner’s strength is low:

- Each step uses a higher percentage of their available capacity

- Fatigue accumulates faster – even at “easy” paces

- Tissues reach their tolerance limits sooner, especially late in runs or during higher-volume blocks

In practical terms, weak runners run “hard” even on easy days.

This is also why so many running injuries:

- Appear gradually

- Show up after mileage increases

- Or emerge late in sessions, not at the start

Modern runner assessments increasingly rely on objective force measurements because mileage, pace, and appearance don’t tell us how close an athlete is operating to their ceiling.

Strength standards help answer a more useful question:

Do you have enough capacity to absorb the forces of running – repeatedly – without breaking down?

What “Strength” Actually Means for Runners

One of the biggest misconceptions in running is that strength training should look “functional” – meaning:

- Light loads

- High reps

- Mostly single-leg work

As outlined by Paul Wilson in VALD Health’s work with endurance runners, this approach often fails to provide enough stimulus to prepare runners for the real demands of the sport.

Despite being a bodyweight activity, running places substantial load on the lower body – particularly through the calf–Achilles complex and knee during stance and braking.

Effective strength training for runners should:

- Expose the athlete to higher loads than running itself

- Increase peak force and rate of force development (RFD)

- Build a larger strength reserve between running forces and maximal capacity

This reserve is what allows runners to tolerate volume without constantly flirting with tissue failure.

Key Strength Benchmarks for Runners

Total Body Strength

Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull (IMTP) is commonly used to assess maximal force capacity.

Benchmarks referenced in the VALD framework:

- <3.0× bodyweight → suboptimal

- 3.0–3.5× bodyweight → good

- >4.0× bodyweight → ideal

Runners below these levels are often operating too close to their ceiling — even before considering asymmetries or tissue-specific weaknesses.

Joint-Specific Strength Benchmarks

Because running injuries are often tissue-specific, joint-level force testing adds important clarity.

Common thresholds used in return-to-run decision making include:

- Hip Iso-Push: ≥ 2.0× system weight

- Knee Iso-Push: ≥ 3.5× bodyweight

- Ankle Iso-Push: ≥ 2.75× bodyweight

- Hip Abduction: > 125 N

These benchmarks help ensure that – regardless of injury history – the runner is prepared for the high-load and high-volume demands of endurance running

Some other hip-specific strength standards I’ve seen cited before in the rehab realm is hip abduction strength <35% of total body weight, and hip external rotation strength <20% of total body weight was predictive of ACL injuries (Khayambashi et al, 2015). These can be tested on dynamometers and could act as an actionable and measurable strength standard to ensure runners are less likely to sustain devastating knee injuries.

Asymmetry Still Matters

Strength isn’t just about absolute numbers. As a general guideline:

- <10% side-to-side asymmetry is commonly used as a “passing” threshold before progressing running load, speed, or plyometrics

- We like to use the phrasing: “as asymmetries approach and exceed 15%, this warrants flagging and addressing”

Asymmetries often persist quietly until volume or intensity increases — which is why they’re frequently uncovered after a setback, rather than before.

Are There Calf Raise “Standards” for Runners?

When it comes to running, some of the muscles and tendons that experience the highest load are the calves (soleus, gastrocnemius), and the Achilles tendons. Scan these stats to see just how high the loads are through these areas:

- Achilles tendon forces commonly reach 6–10 times body weight (or more) during running, with values like 6–8× BW frequently cited for typical speeds, and up to 8–10× BW (or even 12× BW in older classic studies) at faster paces.

- The soleus (deeper calf muscle) bears the majority of this load, often producing forces around 8× body weight (or more) during propulsion, especially at moderate to high speeds.

- The gastrocnemius contributes less, typically around 3× body weight in similar conditions.

Because of these extremely high forces experienced by these muscles, these areas are often ones we put a big focus on both in rehab but also in “injury prevention” programs or general strength programs for runners. For these reasons, there are commonly cited calf raise benchmarks in the literature and clinical practice – but they come with important limitations:

Commonly Referenced Calf Raise Benchmarks

Across sports medicine and physiotherapy literature, typical standards include:

- Single-leg heel raises to fatigue

- General population: ~20–25 reps

- Active individuals / runners: 25–30+ reps

- Performed with:

- Full range of motion

- Controlled tempo

- Minimal trunk or knee compensation

These are often used as screening tools, particularly in Achilles rehabilitation. But keep in mind that calf raises alone are pretty low-load in comparison to the loads the calves feel during running (see the last section for exact numbers).

Jill Cook, a popular tendon researcher and “GOAT” (greatest of all time) by some people’s standards, proposes that in the later-stages of rehab for runners rehabbing an Achilles tendon injury, specifically, that they should be able to work up to 2-3 sets of 5 reps of single leg calf raises with their bodyweight PLUS their bodyweight on the bar on top of that. With that, the runner would demonstrate great calf strength that would likely tolerate the high forces experienced while running.

These are all fine and dandy, but when we consider the speed, the load (more load with faster speeds), and the type of contraction of the calves (less full ROM and more isometric contraction types in high speed sprinting, for example), calf raises aren’t where your training program should end.

Why Calf Raise Counts Fall Short

While calf raise endurance tests (ie. the standard of being able to do 30 reps per side) are easy to administer, they don’t reflect the true demands of running.

Key limitations:

- They assess endurance, not maximal force capacity

- Load is fixed at bodyweight

- They don’t capture:

- Peak force

- Rate of force development

- Ability to tolerate high, fast loading

- That running requires multiple times bodyweight through the lower limb

A runner can perform 30+ heel raises and still:

- Be underprepared for high ground reaction forces

- Have insufficient strength reserve

- Break down at higher speeds or volumes

This mismatch is why many runners “pass” calf raise tests but still develop:

- Achilles tendinopathy

- Calf strains

- Plantar fascia symptoms

When Strength Is No Longer the Limiter

Occasionally, runners exceed relative strength targets (e.g. IMTP >4.0× BW).

In these cases, the focus shifts away from maximal force and toward how well that force is used, using measures such as:

- Dynamic Strength Index (DSI)

- Countermovement jump performance

- Hop testing with ground contact time (GCT) and RSI filters

This ensures the runner isn’t just strong — but able to express force quickly, which matters for stiffness, efficiency, and injury resilience

Movement Standards

Strength provides capacity – but movement determines where the load goes.

Alongside strength benchmarks, there are a few movement qualities I still want to see in runners:

- Minimal hip drop during running

- No excessive heel whip

- Clean squat and single-leg squat mechanics

- Adequate ankle dorsiflexion (10-15cm on a wall test) and thoracic rotation

- Controlled pronation rather than collapse

These principles are well outlined in the literature, and they form a core part of how we teach gait analysis and troubleshooting. That said, many movement issues resolve quickly once true strength deficits are addressed, which is why strength remains the primary filter.

Bringing This Into Practice

Most runners don’t need:

- More mileage

- More drills

- More random “activation” work

They need to know whether their body can actually tolerate the forces of running – and where the gaps are if it can’t.

Objective strength standards provide:

- Clear targets

- Better programming decisions

- Fewer surprises mid-season

Want to Learn How to Assess This Properly?

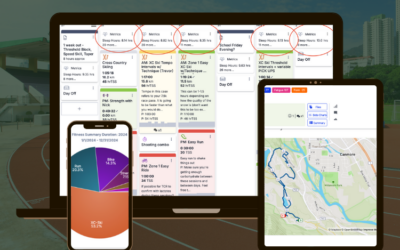

These concepts – strength testing, gait analysis, asymmetry thresholds, and movement screening – are taught in depth at The Conditioning Workshop, coming to Calgary on March 14-15, 2026.

It’s a hands-on weekend focused on:

- Testing standards for runners

- Gait analysis across speeds

- Connecting assessment data to smarter training decisions

Spots are limited, sign up HERE.

If you found this helpful, subscribe to my newsletter The Physiology Toolkit (below). You’ll get user-friendly strength, rehab, and training breakdowns tailored for coaches, athletes, and fitness enthusiasts who want science-backed advice without the fluff.

Or, join us at The Conditioning Workshop to get a deep dive into how to better coach and fix running, cycling, or skating gait, program conditioning for any sport, take your athletes through rehab progressions related to common conditioning related injuries, and overall… take your athletes to the next level by becoming a better coach.

References

- Almonroeder, T., Willson, J. D., & Kernozek, T. W. (2013). The effect of foot strike pattern on Achilles tendon load during running. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 41(8), 1758–1766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-013-0819-1

- Bogduk, N., Pearcy, M., & Hadfield, G. (1992). Anatomy and biomechanics of psoas major. *Clinical Biomechanics, 7*(2), 109-119.

- Dorn, T. W., Schache, A. G., & Pandy, M. G. (2012). Muscular strategy shift in human running: Dependence of running speed on hip and ankle muscle performance. Journal of Experimental Biology, 215(Pt 11), 1944–1956.

- Ferber, R. Running Mechanics and Gait Analysis

- Franz, J. R., et al. (2024). Achilles tendon loading during running estimated via shear wave tensiometry: A step toward wearable kinetic analysis. Journal of Applied Biomechanics. (Published online ahead of print; see PubMed PMID: 38240495).

-

Khayambashi, K., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K., & Powers, C. M. (2016). Hip muscle strength predicts noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in male and female athletes: A prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(2), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546515616237

-

Komi, P. V., Fukashiro, S., & Järvinen, M. (1992). Biomechanical loading of Achilles tendon during normal locomotion. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 11(3), 521–531

- Michaud, T. Injury-Free Running, Second Edition

- Monte, A., Bazzucchi, I., & Felici, F. (2021). Quantifying mechanical loading and elastic strain energy of the human Achilles tendon during walking and running. Scientific Reports, 11, Article 5833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84847-w

- Powden, C. J., et al. (2022). The load borne by the Achilles tendon during exercise: A systematic review of normative values. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. (See PubMed PMID: 36278501).

- Reiter, A. J., Martin, J. A., Knurr, K. A., Adamczyk, P. G., & Thelen, D. G. (2024). Achilles tendon loading during running estimated via shear wave tensiometry: A step toward wearable kinetic analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 56(6), 1077–1084. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003396

- VALD Health. Optimizing Endurance Running Performance and Rehabilitation: A Q&A with Paul Wilson